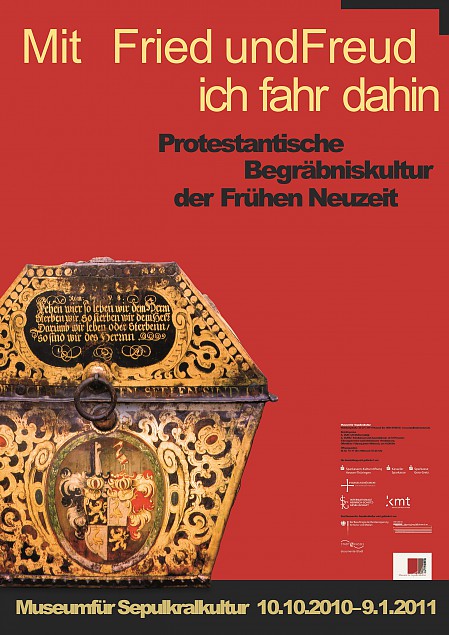

10. October 2010 – 9. January 2011

Protestant funeral culture of the early modern age

Joint Exhibition With the City Museum Gera on the Occasion of the International Heinrich-Schütz Festival in Kassel

The Reformation in the 16th century changed the world, including people's attitudes towards dying and death and thus also the burial practice and cemetery culture. The human being becomes the focus of the funeral celebration and remembrance, which cannot be understood without the newly awakened self-confidence of the people in the Renaissance.

Martin Luther, originator and teacher of the Reformation, wanted to help a bible-based theology and piety find new life: The reformers agreed that the deceased did not need the relative’s intercession and that there was no purgatory. The place of the grave was thus no longer bound to the salvific proximity of the church and the relics of the saints. Therefore, all 'superstitious' ceremonies, soul masses, intercessions and good works to come were to be renounced in favor of the deceased. For Luther, the funeral became a proclamation of the Gospel and a consolation for the mourners, but also a reflection on his own finiteness. In 1519, he wrote a sermon with advice on how to deal with death and mourning and how to prepare for death – a forerunner of the funeral sermon. This quickly developed into an important medium of Reformation funeral practice, which increasingly focused on the appreciation of the deceased. Depending on the social status, it could be elaborately designed. Music became a central component of the funeral service. For this purpose, Luther put together a collection of funeral songs, such as "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin" (With peace and joy that is where I go). The construction of cemeteries outside the villages became the norm, from a hygienic, economic and theological point of view. While these were often rather unadorned, members of the upper class, who until then had enjoyed the privilege of burial in church, were given cemetery walls with arcade halls and crypts, in which they erected tomb monuments or painted epitaphs with biblical images and representative family depictions.

Designing coffins with biblical texts, verses from hymn books and long biographical inscriptions of the deceased also gains importance. Thus, the new Protestant piety is reflected in the emphasis of the words on gravestones and coffins but also in music. This is documented in a unique way by the painted biblical inscriptions and choral verses on the famous ceremonial coffin of Heinrich Posthumus Reuß (1572-1635). While still alive, he selected biblical texts and hymnal verses which were to be the basis for the funeral service and coffin inscriptions. Heinrich Posthumus Reuß was the first in the Protestant area to leave a fully inscribed sarcophagus with an individual concept - a fully formed confession of faith in combination with Bible verses and hymnal verses. On the occasion of his funeral, the most important German musician of his time, Heinrich Schütz, set these texts and the "Musical Exequia" to music.

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Friedhof und Denkmal e.V.

Zentralinstitut für Sepulkralkultur

Museum für Sepulkralkultur

Weinbergstraße 25–27

D-34117 Kassel | Germany

Tel. +49 (0)561 918 93-0

info@sepulkralmuseum.de