CEMETERIES AROUND THE WORLD

We travel all over the world and report on the funeral and cemetery culture of countries, religions and cultures. The photo journeys are selected for their particular topicality or special features. The collections shown here are intended to document transformative processes and continued traditions. The photographs and travelogues thus provide an insight into the diversity of the sepulchral culture.

The tulip cemetery in Gönningen

True tulip splendor

Every spring, from mid-April onwards, a sea of blooming tulips attracts crowds of visitors to the Gönningen cemetery. On the graves as well as on open spaces along paths and on meadows, tulips in different colors and shapes offer a feast for the eyes. Many places in Gönningen are adorned with tulips, and for some years now the cemetery has once again been one of them.

The close connection between Gönningen and tulips has historical reasons, about which the seed trade museum in the Gönningen town hall provides information. The small town at the foot of the Swabian Alb was a center for the seed trade from the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century. At times, almost half the population traveled throughout Europe and beyond to sell flower and vegetable seeds and tulip bulbs. Back home, people also enjoyed tulips in gardens and planted the then very valuable tulip even on graves.

Beyond private tulip plantings, nowadays the Gönninger Tulpenblüte association is committed to the annual emergence of the abundance of flowers. In addition, the show garden of the family-owned company Samen-Fetzer, founded in Gönning in 1865 and located not far from the cemetery, attracts the interest of tourists with its large assortment of spring blooming plants, including many varieties of tulips. In comparison, the small cemetery is a tranquil place where the tulips can be viewed "applied" in peace: In the cemetery they continue bourgeois commemorative culture of the late 19th century, in which the deceased were commemorated with elaborate and precious grave decorations. Besides, the tulips also participate in the proud self-confidence of a community in its specific and special commercial history. It is certainly a challenge to keep the different aspects of this cemetery – as a place of personal remembrance, as a historical testimony and as a magnet for tourists – in a balance, where the former aspect is not overstrained.

Report: Dagmar Kuhle/ Photos: Peter Trump

The Eichbühl cemetery in Zurich

A special design concept

The Eichbühl cemetery in Zurich is an exceptional cemetery. This is due to its almost unique design concept, on which the opinions diverge since its inauguration in 1968. Regardless of individual subjective aesthetic judgement, the concept is one thing in any case: radical!

The cemetery is located in the west of Zurich, in the Altstetten district. It is located at the northern end of the Albis mountain range, the Uetliberg. What makes it so radical, and thus so striking, is its highly economical concrete architecture in the midst of a vast natural landscape, which provides an extremely exciting contrast.

The most important architectural structures – entrance terrace with a laying out hall, chapel, large pavilion with basin – are arranged in such a way that they form an imaginary triangle in the landscape and are immediately at different levels.

No less striking are the six large grave fields cut into the foot of the slope, which – surrounded by walls – (should) offer intimate burial spaces. Over the many years, however, it has become apparent that the capacity of the cemetery has fallen far short of the former expectations – at that time, projections showed a demand of 18,000 graves.

The cemetery was designed and created by the teams of architects Hans Hubacher and Ernst Studer (architects), Ernst Graf and Fred Eicher (landscape architects) and the sculptor Robert Lienhard. It provided for additional trees, shrubs, hedges and perennials with the aim of breaking through the austerity of the site and ecologically upgrading the area. Two decades later, this was abandoned (2005), as it was now considered desirable to make the radical clarity of the original landscape architectural design tangible again. However, Lindenallee, which was laid out in 1987 and which you pass directly from the entrance terrace to the pavilion, was – one could say: fortunately – excluded from the concept revision.

Over the years, the measures to change and revise the concept have repeatedly given rise to discussions. This underlines once again that the Eichbühl Cemetery is a very special facility in the service of the Last Rest. It reveals a highly individual and thus highly extraordinary charm, which makes a visit in any case recommendable.

Photos: Ulrike Neurath

white marble and artificial flowers

The Greek Orthodox cemetery on the Cyclades island of Mykonos

The Greek Orthodox cemetery on the Cyclades island of Mykonos is located, like almost all Greek cemeteries, outside the village, at the edge of the small village of Ano Mera in the center of the island. You can see very beautiful and elaborate marble gravestones with large white grave slabs and interesting sculptures, some with a glass case containing candles, photos and souvenirs of the dead. A beautiful marble landscape for above and below ground graves and various grave decoration with portrait photos. Fresh flowers are almost never found, but a sea of plastic flowers or wreaths, which does not mean that the relatives do not visit the grave. Regular burials are as common here as in Germany. As usual, there is also a small Greek chapel, which is used for laying out and blessing. Since cremations are unusual in Greece (legalized in 2006), you will only see burial graves here as well. After three to four years the bones are taken out of the grave, washed, cleaned and doused with red wine. Then they are bundled, wrapped in cloth or put in a container and laid out further in a niche with a name plate in the family chapel or in the so-called ossuaries. The burial is thus only an interlude.

Photos: Achim Eckhardt

The cemetery of Porreres, MALLORCA

Burial chambers and Crypts

When you enter the cemetery of the Mallorcan town of Porreres, which has a population of around 5500, you immediately notice the literally diverse architecture and formal language with an almost uniform colour scheme. The buildings as well as the graves and tombs have a yellowish colour, just like many houses of the village itself, which are sandstone buildings. Everything blends harmoniously into the surrounding landscape, which follows this colour style especially in the hot late summer.

The cemetery of Porreres is especially impressive in beautiful weather. This is not only due to the glory of sunshine and blue sky, but also to the fact that it creates an enormous colour contrast, which makes the resting places of the dead appear in a fascinating way. Beside many single, but specially family graves that are covered with grave plates (tomb graves), there are columbaria and/or grave niches arranged under and above ground, as well as numerous tomb buildings. The latter are family graves that are each closed with a narrow iron gate and also contain multi-storey grave niches. As these tombs partly line the cemetery area, they remind of a camposanto, i.e. a type of cemetery whose above-ground crypt chambers enclose the entire burial area like a courtyard. The classical Cemetery also has an arcade opening onto the "courtyard" - alternatively a colonnade - which is not the case in the Porreres cemetery.

Despite the dominance of the sandstone-yellow colour, there are also other spots of colour, although very reduced. These are formed by various grave accessories, which are only a bit more luxuriant on some children's graves. In addition, splashes of colour are recruited from the flower and plant decorations, which are also usually clearly arranged. Especially small (artificial) bouquets of flowers adorn the grave niches, where they are fixed directly to the front plate or are placed in vessels or vases.

In 2016, the Porreres cemetery attracted attention beyond Mallorca, as a mass grave with the remains of 71 people was found there. The dead were "republicans", i.e. the supporters of a democratically elected government of the so-called Second Spanish Republic, who were executed by right-wing "nationalists" during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

Photos: Ulrike Neurath

Christmas at the cemeteries in Iceland

Akureyri in the north and Borganes in the west

Daylight is a rare ressource on Iceland in winter. But artificial lighting is omnipresent in towns and cities since human beings started to see nature as an energy source and perfected its use. Even cemeteries are brightly lit by street lamps. But it is rather unusual for foreign visitors that at Christmas time the individual graves are also decorated with electrically illuminated crosses.

On newer cemeteries, such as the cemetery above the city of Akureyri (Icelandic so-called "capital of the north", 90km south of the Arctic Circle), it is tradition to transform the cemetery into a shining work of art – with many sockets and a design specification regarding the crosses to be used.

In the cemetery of the small village of Borganes (70km north of Reykjavík), however, a wide variety of crosses shine in front of the graves, there is no design specification here. And a closer look reveals a rather improvised tangle of cables between the gravestones.

The origin of this custom is not conclusively clarified. However, even before Christianity entered Iceland, as in other Scandinavian countries, the shortest and thus darkest day of the year (December 21) was celebrated with a "festival of lights". On this date, from which the days become longer again, all houses were decorated with oil lamps and candles. So it seems obvious to honour the dead with lights as well. In Norway, by the way, it is still customary today to place burning candles on the graves at Christmas.

In the harsh conditions of the Icelandic winter, which before the climate change from October to April brought a closed snow cover with a lot of wind, the first electrical variants of grave decoration on the cemeteries quickly caught on. So if you travel through a dark Iceland around Christmas time, you will be greeted everywhere by colourful lights and are reminded of the resting dead.

Photos: Michael Göbel

The Cemitério dos Prazeres

"Cemetery of delights"

The Cemitério dos Prazeres ("Cemetery of delights") is the most impressive "graveyard" in the Portuguese capital. The cemetery was built in 1833 after a cholera epidemic. It is a burial place for aristocrats as well as upper-class intellectuals and artists. It is located in the west of the city and is characterised by its above-ground crypts, the so-called burial villas, which are arranged in streets and avenues. They are closed, but offer the possibility for relatives to enter and mourn their dead at small altars in the presence of the open coffins. The proximity to the deceased is impressive, as it makes it clear that it is not perceived as threatening, unhygienic or disturbing. On the contrary: it reveals the connection between the living and the dead.

Photos: Dirk Pörschmann

Journey through Bosnia and Herzegowina

Remembrance of War and Confessional Grave Fields

Serbs, Croats and Bosnians live close together in the Bosnian Br?ko district on the border region of the three countries. Muslim, Catholic and Serbian Orthodox cemeteries alternate during the journey across the region Br?ko. And thus mostly white stone steles of the Muslim population and black gravestones with photo engravings from the lives of the deceased in the Christian cemeteries.

A small cemetery near Br?ko with mainly Serbian Orthodox graves is located between fields and hills. On the fronts of the red-black gravestones there are often small enamel plates with portrait photos of the deceased, on the backsides large photorealistic engravings from everyday life – with a musical instrument, shotgun or cup in the hand. In the metal cottages next to the family graves there are remains from the lighting of the yellow candle sticks brought along and of incense and charcoal.

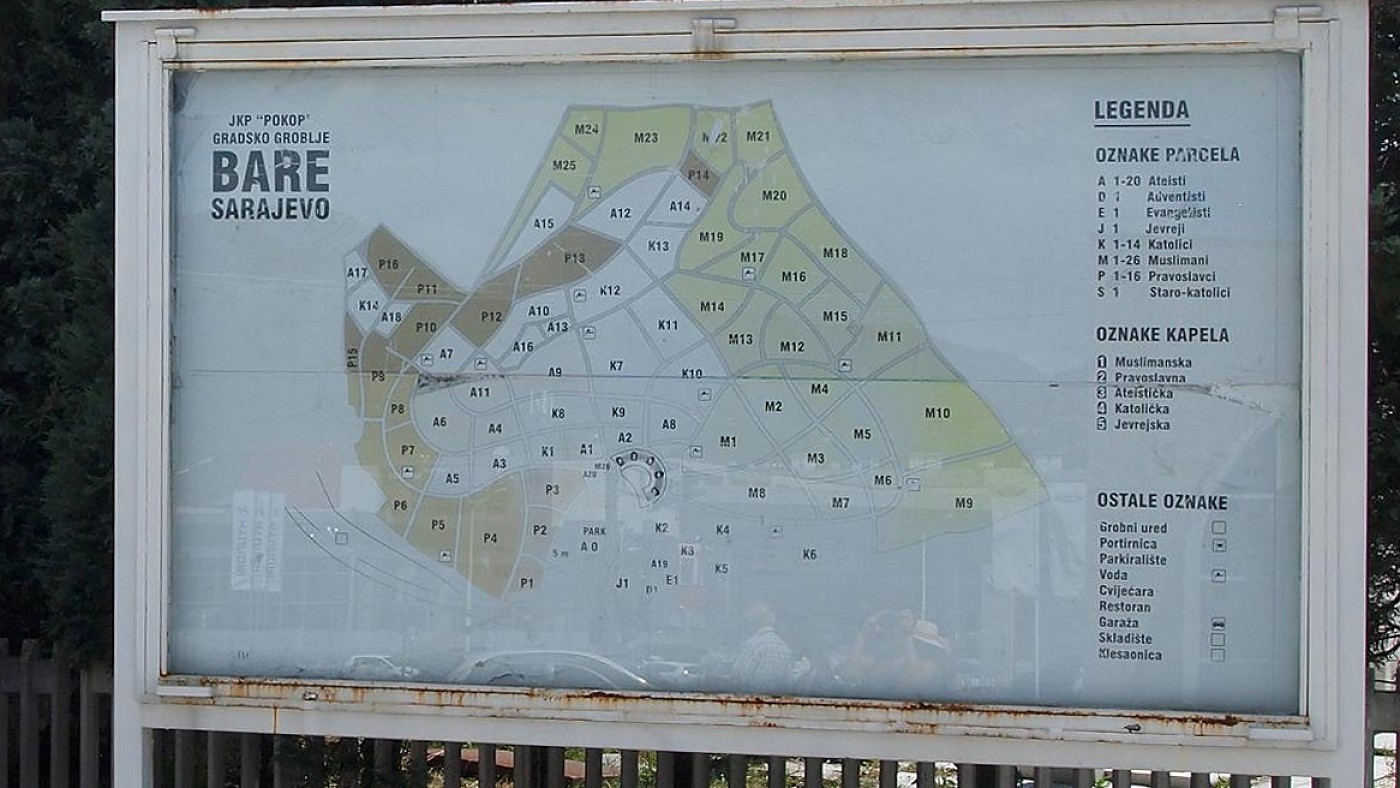

At the Bare Cemetery in Sarajevo, on the other hand, the different burial traditions are very close together. Opened in 1962, the cemetery is one of the largest in Europe. It extends - divided according to denominations - over the hills near the city and gives a picture of the variety of graves and also of the masses of victims of the Yugoslavian wars. In the middle, organically looking chapels arranged in a semicircle are available for the members of the respective denominations - Muslim, Orthodox, atheist, Catholic and Jewish. There are also separate cemeteries for Adventists, Evangelists and Old Catholics. The black and red gravestones are also found in the fields of the Catholic and Orthodox population. But also gravestones with photo engravings and the crescent of Islam are scattered there. The borders between the burial traditions are sometimes blurred on closer inspection. But what is most memorable when leaving or entering the city are the endless rows of graves of the victims of the Yugoslavian wars.

Photos: Tatjana Ahle

Journey to the Isle of Lewis

Between sky and sea

The three Callanish (also Calanais) sites form the largest known megalithic rock formation in the British Isles. It dates back to the Bronze Age (ca. 5000 BCE) and does not consist of a circle, but of several interwoven forms. The largest monolith is 4.5m high. The sense behind the creation of the stone formation is in the dark. The most popular theory says that the stones refer to the course of the moon. Because of its remoteness on the Outer Hebrides, Callanish is less known than Stonehenge, but more accessible. Visitors get – in contrast to the closed Stonehenge – directly to the stones and access is (still) free.

The cemetery of Bosta on the Great Bernera Peninsula of the Isle of Lewis houses war graves like so many places in Scotland. They have been marked by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission which is responsible for these graves. The graves of those who died in the First and Second World Wars are specially protected.

Right by the sea is one of the cemeteries of the Bhaltos Peninsula. Many cemeteries in the Outer Hebrides are characterized by the boundary of a stone wall. They often lie outside the villages. Since the sea is not far away in the Hebrides, they often have a beach nearby and a beautiful view of the sea.

Photos: Isabel von Papen

more about the Isle of Lewis

The Outer Hebrides are islands 60km off the west coast of Scotland, which stretch over 208km across the Atlantic like a string of pearls. The northernmost and largest of these islands is the Isle of Lewis, which together with the Isle of Harris forms a double island. As Harris is separated by a mountain range, people have given them two names. In total, 18.500 people live on the island. Their languages are both English and Scottish Gaelic. The main town of Lewis is Stornoway. In contrast to the Hebridean Islands further south, Lewis has a Presbyterian (Protestant) tradition that still clearly insists on observing the Sabbath: on Sundays, public island life comes to a standstill.

A round trip through Mexico:

On Route 180 between Campeche and Palenque, close to the the Gulf of Mexico, lies a small cemetery

On the small colourful cemetery you will find graves of newer and older dates. Among them are beautifully designed single graves or simply kept ones, often with several grave chambers on top of each other. The newer single graves are mostly tiled and have a window or a small open chamber. Many of them have a cross or an angel on top. Between the simple graves there are only treaded paths. You can see the hot climate, because the paths are strongly weathered. Between the more expensive looking gravestones in the main entrance area, paved paths lead along. What is specially noticeable is the wonderful colourful arrangement of the graves. As if the Mexican life shines towards you, not death. Everywhere one finds remains of the Mexican festival of the dead, the Diá de los Muertos, which is celebrated every year at the beginning of November. On this day, the living spend the night with the whole family at the tomb of their deceased relatives to talk about them and tell each other stories so that they are not forgotten. They decorate the graves magnificently with flowers and candles and carry gifts for their loved ones. These include Pan de Yema, the yeast pastry that is supposed to give the dead strength on their way to their living relatives, chocolate and sugar skulls to strengthen them and candles to light their way. They eat together, drink Mezcal and wait to be touched by the spirit of the dearly departed.

Photos: Regina Oesterling

Arbeitsgemeinschaft Friedhof und Denkmal e.V.

Zentralinstitut für Sepulkralkultur

Museum für Sepulkralkultur

Weinbergstraße 25–27

D-34117 Kassel | Germany

Tel. +49 (0)561 918 93-0

info@sepulkralmuseum.de